Reinforcement Fine-Tuning to Identify Causal Genes with Llama Models

Alt Title: Recreating OpenAI’s reinforcement fine-tuning demo with Llama models

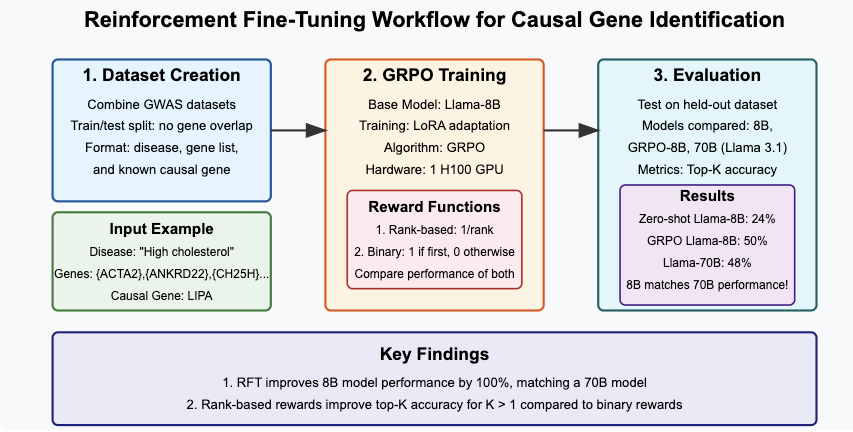

TL;DR - In this post, we will fine-tune Llama models with reinforcement learning to identify causal genes for diseases. This is also an attempt to recreate OpenAI’s demo of reinforcement fine-tuning (RFT) showing that with about 1000 training examples and reinforcement fine-tuning, a smaller model (o1-mini) could outperform a larger one (o1) at the task of identifying genes causing rare disease. We will use a similar task of identifying causal genes, and show that with reinforcement learning, an 8B parameter model can perform as well as a 70B parameter model.

What is “causal gene Identification” and why does it matter?

Before getting into the technical aspects of our experiment, let’s briefly explain what causal gene identification is and why it’s important:

Genes are sections of our DNA that contain instructions for making proteins and other molecules critical for our body’s function. The human genome contains approximately 20,000 genes, but understanding which specific genes are responsible for certain diseases or traits is a complex challenge.

Causal gene identification is the process of determining which specific genes contribute to a particular disease, condition, or trait. This is crucial because it can help develop targeted therapies (e.g cholesterol-lowering drugs targeting PCSK9), better risk prediction for certain conditions (e.g.,BRCA mutations increase breast cancer risk), and personalized medical treatments.

Traditional computational methods to pinpoint causal genes often cannot integrate evidence from publications. Here, we explore how large language models (LLMs), specifically through reinforcement fine-tuning (RFT), can efficiently rank likely causal genes from a list of candidates. For example, given a DNA region associated with heart disease containing multiple genes, our approach trains an LLM on a small dataset to prioritize the actual causal genes, incorporating a new source of evidence. We have previously shown that state-of-the-art models like GPT-4o and Claude can perform zero-shot causal gene identification through literature evidence, and will now try to extend this capability to smaller Llama models.

Motivation

What is reinforcement fine-tuning?

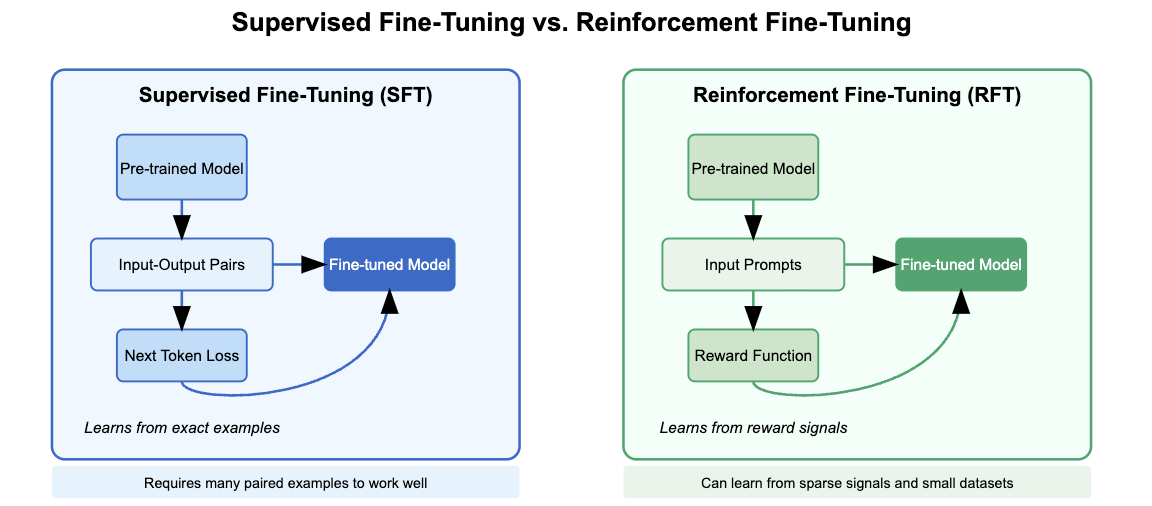

Reinforcement learning (RL) is a machine learning approach where models learn to make better decisions through trial-and-error interactions with an environment, guided by rewards or penalties.

Reinforcement fine-tuning (RFT) applies this RL concept specifically to large language models. Instead of simply showing the model the exact correct answer (as in supervised fine-tuning, SFT), RFT uses a reward system to guide the model towards desired behaviors, even without explicit examples for every possible scenario.

OpenAI demonstrated that RFT enables models to learn complex tasks effectively from very small datasets, even improving tasks beyond simple token matching. A similar framework is also described in the Tulu3 technical report.

OpenAI demo of reinforcement fine-tuning

In the “12 days of OpenAI” OpenAI showed a demo of their “reinforcement fine-tuning”, a new fine-tuning technique using reinforcement learning that allows fine-tuning with a small amount of training data and a grading function that can score the model’s response with reference answers. The main advantages of RFT over supervised fine-tuning is that RFT allows models to (1) learn behaviors beyond exact next token prediction and (2) learn from very small datasets, even those too small too use for supervised fine-tuning.

In the demo, OpenAI showed a task that involved mapping a medical case report to a specific responsible gene. Here, the model was asked to create a ranking of genes by decreasing relevance, and based on the rank of the reference gene in that list, the model received a reward/score (lower ranks = higher scores). They showed that the model weights could be updated to favor outputs that received higher scores.

Open implementations of reinforcement fine-tuning

Since then, we have seen a number of nice RFT implementations (examples: 1,2,3). These have mostly been focused on math problems with a single correct answer, and binary rewards for correct/incorrect answers. However, none of the existing implementations look at tasks in genetics or have ranking-based rewards. Ranking-based rewards are potentially interesting since binary (0/1) rewards for correctness only offer a model limited signal (“sparse rewards”), while ranking-based rewards offer a more fine-grained signal (“dense rewards”).

Our goal

We will recreate the causal gene identification task in the OpenAI demo using reinforcement learning in a related but slightly different setting to answer these questions.

- Question 1: Can we use RFT to improve the performance of models at causal gene identification?

- Question 2: What is the benefit of ranking-based rewards over binary rewards?

We will use results from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) linking DNA to traits/diseases and try to identify relevant genes in specific regions of the genome. While OpenAI’s task focused on identifying relevant genes for symptoms from single person’s case report, our task will be to identify relevant genes for a symptom/trait studied in an entire population. We will use a rank-based reward that will give the model a score based on what rank it assigned to the known causal gene.

First, we will describe our problem setting and its analogy to the task from the OpenAI demo. Then we will describe our implementation. We will evaluate our results and check if we see performance improvements. We will end by summarizing all the lessons learned from trying to recreate this demo.

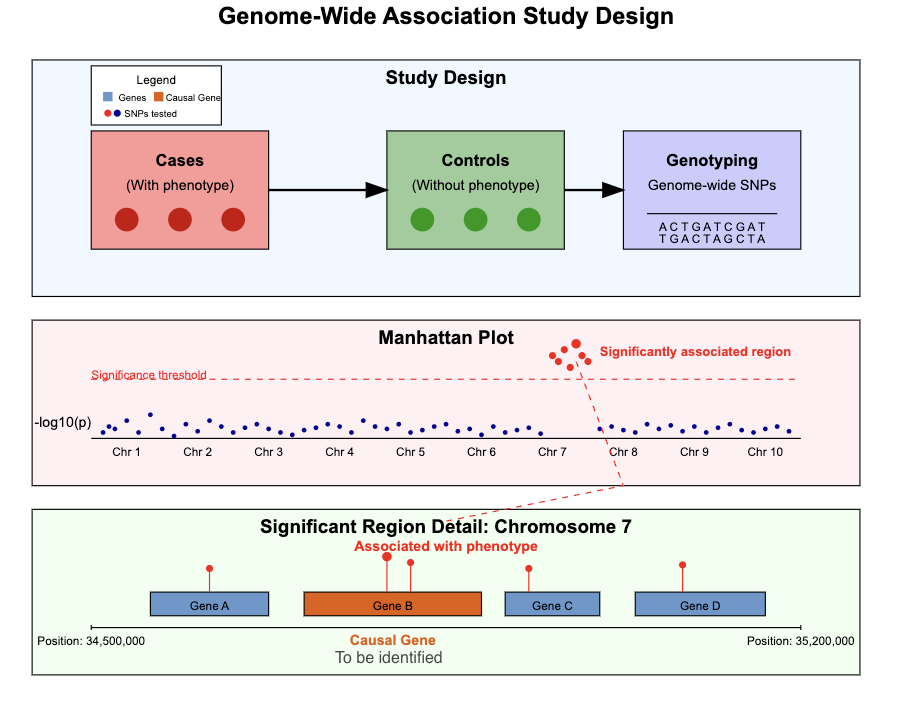

Problem

We will use an LLM to identify likely causal genes for a disease/trait from results of genome-wide association studies (GWAS). The premise of genome-wide association studies is that if a trait/disease has a genetic basis, then there will be statistically meaningful differences between the DNA sequences of people who have the disease (called cases) to those of people who don’t have the disease (called controls). Any regions that show a difference could be responsible, acting through one of the genes in or around the region. Such a gene is considered a causal gene for the disease.

In practice, the LLM will receive as input the name of the disease and a list of gene names, and it will be asked to rank the provided genes in terms of their relevance to the disease. This is similar to the OpenAI task, where the input was a medical case report describing the patient’s symptoms, and the model was asked to produce a ranked list of genes relevant for the symptoms.

We have previously described the use of LLMs for the task of identifying causal genes from GWAS in a preprint. State-of-the-art LLMs perform competitively/outperform existing computational methods at this task. We will use some of the datasets from this preprint for our task. We will try to train smaller LLMs to do this task using reinforcement learning.

Implementation

The implementation involves two main steps:

- Dataset Creation: Prepare a dataset of examples with (disease, list of candidate genes, correct gene) with appropriate train/validation/test splits.

- Model Training: We will use Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) from the Hugging Face

trllibrary andunslothfor our reinforcement learning on a Llama 3.1-8B model.

Before diving into the details, here’s a visual overview of our approach:

Code for the implementation is at https://github.com/suyashss/rft_demo.

Step 1: Dataset creation

To ensure sufficient examples for training and evaluation, we combine two datasets with known causal genes to create our datasets for this task, a training set and a held-out evaluation set. We filter these so that the causal genes in the evaluation set and the training set have no overlap. More details of the data preparation are in setup_datasets.py. Every example in the dataset now has the three fields for training:

- Disease/trait name: This is a short description of the disease or trait.

- List of genes in region: This is a gene list represented as a string, with each gene enclosed in parentheses. Each gene is represented by its symbol, e.g. BRCA1.

- Known causal gene: This is one of the genes that is part of the gene list above. This is established in the dataset by different sources of evidence - for example, the gene whose protein is a target for a drug approved for the disease in the example.

The data we used is hosted on 🤗 Hugging Face and available for download at suyashss/gwas_genes.

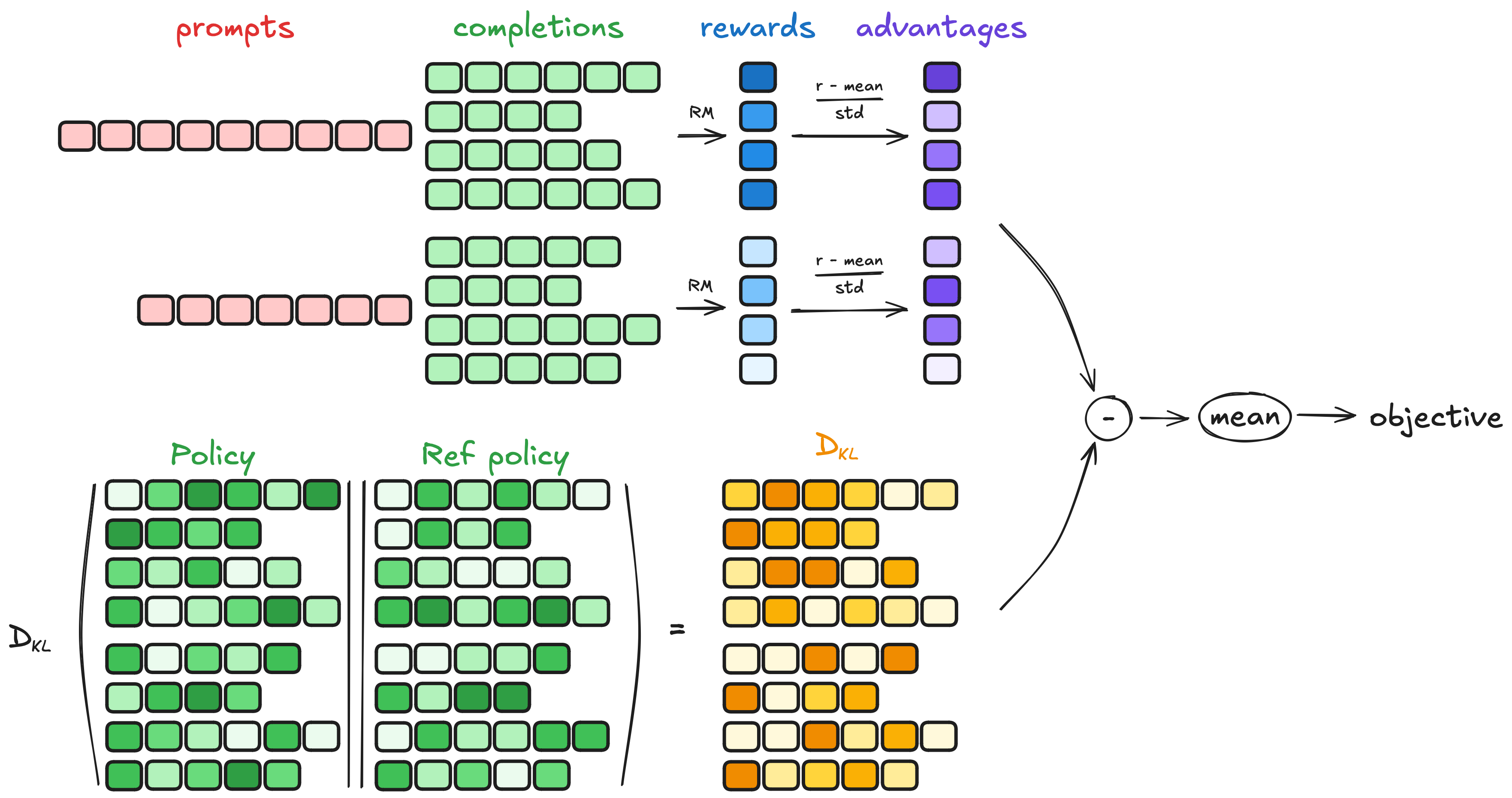

Step 2: Reinforcement learning

For reinforcement fine-tuning, we used the Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) algorithm. GRPO was first developed by DeepSeek in their DeepSeekMath paper. The main improvement was that the advantage term needed to compute the loss function was computed by comparing the rewards within a group of completion, without needing a value model. This makes GRPO more memory-efficient. The image below from Hugging Face shows how GRPO works.

We use the GRPO implementation from the trl library. One of the main advantages of GRPO is the smaller number of model copies that we need to keep in memory, making memory requirements easier to handle. In addition, instead of a full fine-tuning, we will use low-rank adaptation (LoRA), which will update a much smaller number of parameters than the full 8B. All this means that we can run GRPO fine-tuning on Llama-8B on a single A100 GPU with 80GB VRAM. Thanks to the unsloth team for enabling this - they have an detailed blog post and guide about this, and we used most their recommended configuration for our training.

Reward functions

Since we use a relatively large (8B parameter) model, we simplify our reward functions to only use a single reward function for correctness (and exclude formatting reward functions). Our correctness reward function takes as input the prompt, the completion, and the true causal gene.

From the completion, it extracts the ranked list of genes, and checks the position of the true causal gene in that list. If the gene is in the list, the rewards is 1/rank else the reward is 0. The table below shows the reward values for rank-based rewards and binary rewards. As the rank of the causal gene increases, the rank-based reward smoothly decreases. In contrast, the binary reward abruptly drops to 0 if the causal gene is not at rank 1. The rank-based reward thus gives the model partial credit for ranking the causal gene closer to rank 1, which could improve top-K accuracy for K > 1.

| Rank of causal gene | Rank-based reward | Binary reward |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 2 | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| 3 | 0.33 | 0.0 |

| 4 | 0.25 | 0.0 |

| 5 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

The rank-based reward is easy to implement in trl by using their reward function framework.

def correctness_reward_func(prompts, completions, answer, **kwargs) -> list[float]:

responses = [completion[0]['content'] for completion in completions]

extracted_responses = [get_gene_list(r) for r in responses]

return [1.0/(1+r.index(a)) if a in r else 0.0 for r, a in zip(extracted_responses, answer)]

Fine-tuning on Modal

We use Modal to get access to larger and faster GPUs, and use 1 H100 GPU for training. The full run took about 12 hours and cost about $50. The script to run GRPO on Modal is at run_grpo.py.

@app.function(

volumes={MODEL_DIR: volume}, # "mount" the Volume, sharing it with your function

image=rft_image, # only download dependencies needed here

secrets=[modal.Secret.from_name("wandb")], # huggingface token

timeout=3600*24, # set longer timeout for training

gpu=GPU_CONFIG

)

def launch(

model_name: str, hf_dataset_name: str, output_dir: str, hf_dataset_config: str = 'default',

lora_rank: int = 32

):

model, tokenizer = setup_model(model_name, lora_rank)

train_ds, eval_ds = setup_dataset(hf_dataset_name, hf_dataset_config)

results_dir = MODEL_DIR / output_dir

results_dir.mkdir(parents=True, exist_ok=True)

training_args = setup_training_args(str(results_dir))

from trl import GRPOTrainer

trainer = GRPOTrainer(

model = model,

processing_class = tokenizer,

reward_funcs = [binary_reward_func],

args = training_args,

train_dataset = train_ds,

eval_dataset = eval_ds,

)

trainer.train()

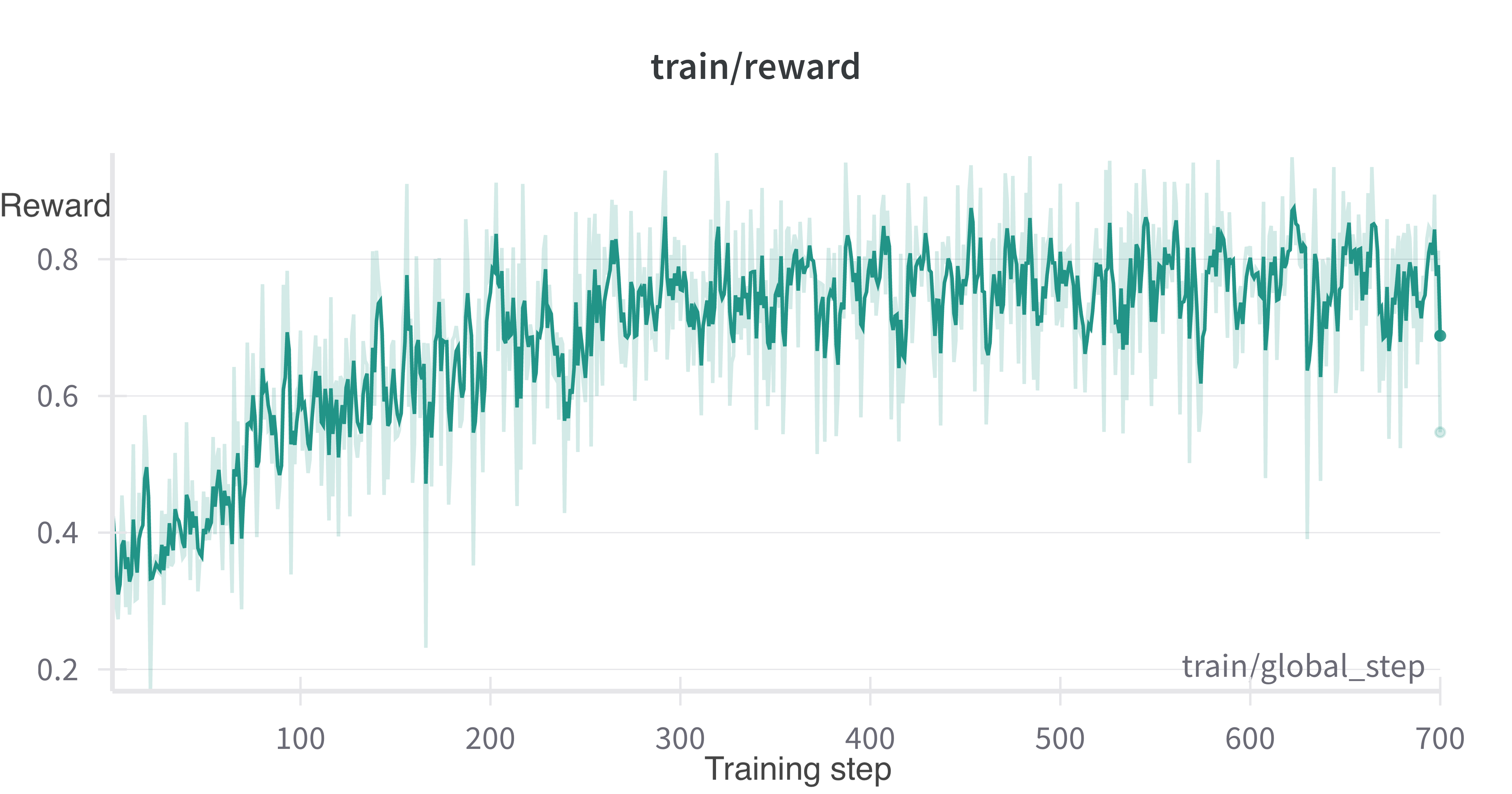

We find that training proceeds as expected, with the training reward increasing from about 0.35 at the start to nearly 0.8 by the 10th epoch. Since our reward function is reward = 1/(rank of causal gene), that shows the causal gene rank improves on average from 3 to 1.25.

WandB training logs for the run are available here. Note that the “eval” metrics in the logs are 10% of the original training set that we use as a validation set, with the remaining 90% used for GRPO training.

Evaluation

On the training data, we can see that model performance improves. To evaluate performance on the test set, I used vllm for inference, again using Modal for multi-GPU inference for Llama-70B. The inference script is run_vllm_inference.py. All models used were Llama 3.1 for similar training data cutoffs.

Does RFT help causal gene identification?

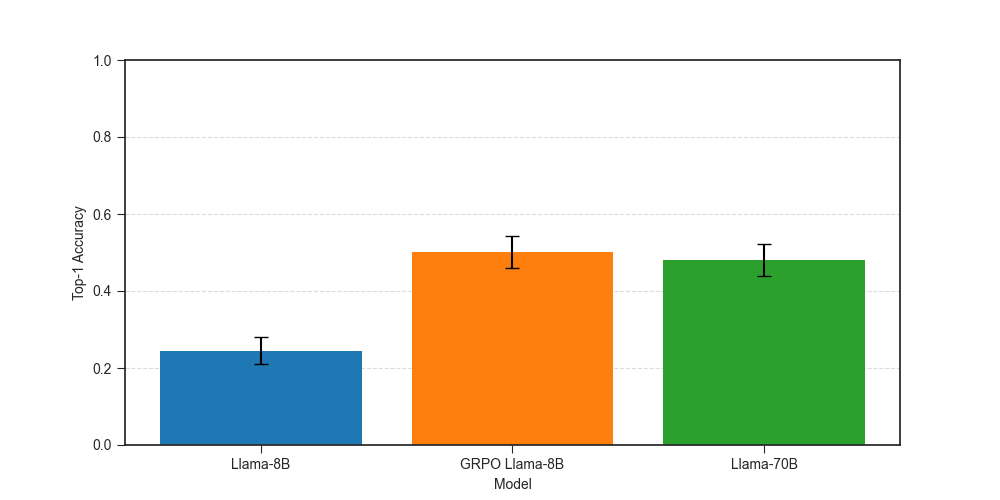

We use top-1 accuracy as our metric for comparing performance of different models.

Top-1 accuracy improves from 0.24 for zero-shot Llama-8B to 0.50 for the GRPO Llama-8B, a 100% improvement! Our GRPO-tuned model matches the performance of Llama-70B, which has top-1 accuracy of 0.48. The difference between the two is not statistically significant, given our relatively small evaluation dataset of ~270 examples. It is pretty amazing that we can match the performance of a 9x larger model by fine-tuning on about 600 examples.

Answer: Reinforcement fine-tuning improves the performance of Llama-8B at causal gene identification.

Our results align well with the results shown in the OpenAI demo, where the top-1 accuracy of o1-mini improved from 0.17 to 0.31, surpassing o1’s accuracy of 25%, with a similar pattern for top-5 accuracy.

Do rank-based reward have advantages over binary rewards?

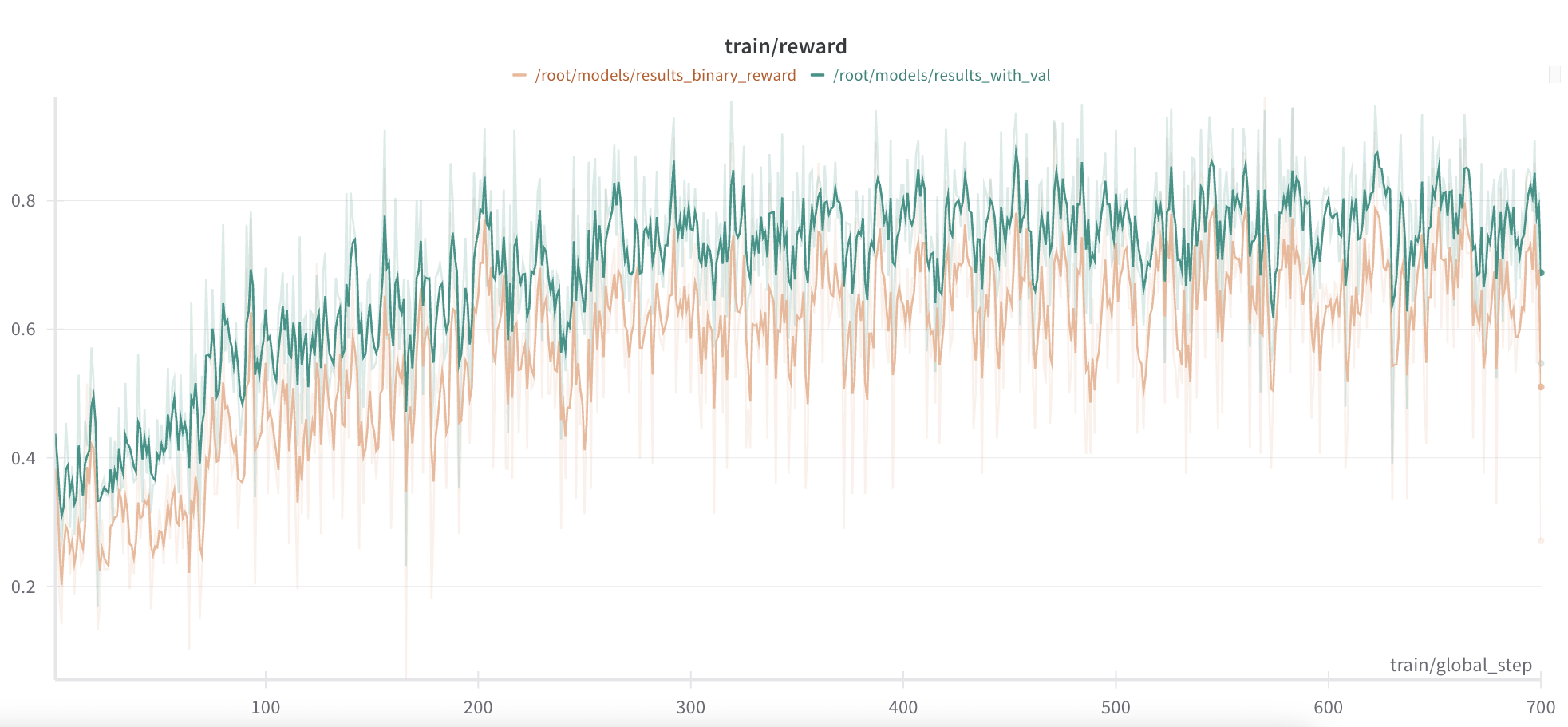

Let’s now look at question 2 (“What is the benefit of ranking-based rewards over binary rewards?”). For this, I re-ran the GRPO training with a binary reward function, with a reward of 1 if the causal gene was ranked first in the respone, else a reward of 0.

def binary_reward_func(prompts, completions, answer, **kwargs) -> list[float]:

responses = [completion[0]['content'] for completion in completions]

extracted_responses = [get_gene_list(r) for r in responses]

return [1.0 if len(r) >=1 and a==r[0] else 0.0 for r, a in zip(extracted_responses, answer)]

We train the model for the same number of epochs as our original run. If we look at the training reward curves for the two approaches, those look quite similar, with the binary reward being consistently smaller than the rank reward, but only slightly.

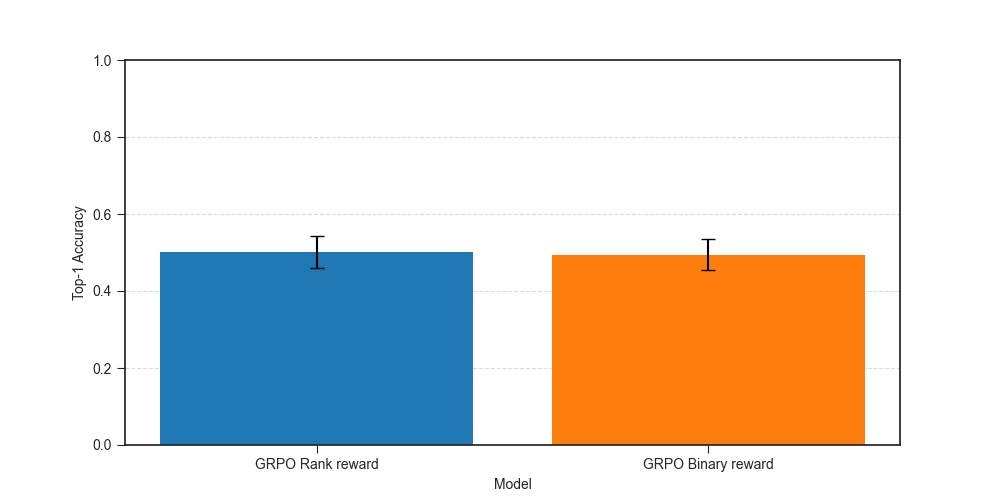

Looking at accuracy, we find no significant difference between the top-1 accuracy of the two approaches.

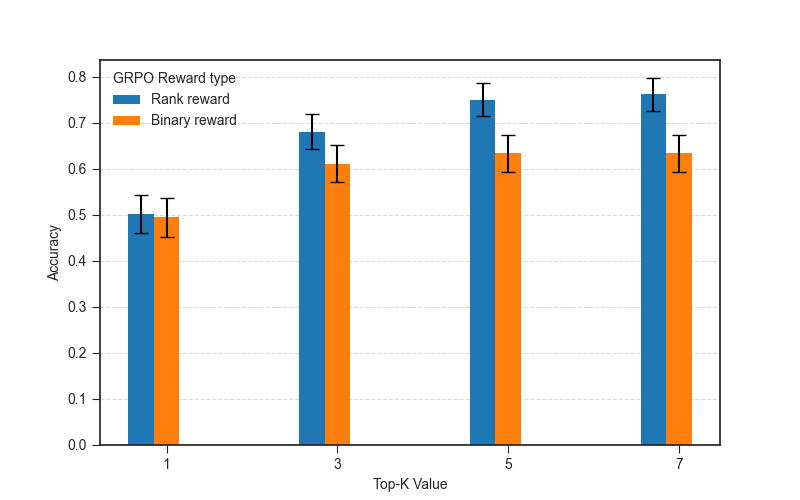

At first glance, this suggests no benefit from the ranking based reward. But the rank-based reward encourages the model to rank the causal gene closer to the top even if it doesn’t rank it first, so it might help improve top-K accuracy for K > 1. If we look at top-K accuracy for different values of K, we see that the performance of GRPO with rank-based reward becomes better than that with the binary reward as K increases, and is statistically significantly better after K >= 5.

Answer: Rank-based reward helps improve top-K accuracy for K > 1, but at least for causal gene identification, top-1 accuracy is the same for binary and rank-based rewards.

Lessons learned

This was a very interesting exercise, and I learned a lot of new things. Some of the major lessons learned along the way:

- Dataset curation continues to be important: Labeled datasets in this domain are hard to obtain, and often biased in their own unique ways. Of the two datasets I used, a model trained on only one dataset did not transfer well to an evaluation on the other since they focus on different kinds of gene-phenotype relationships. To match train-test distributions, I ended up combining the datasets and randomizing to create train-test splits.

- RL is easier on larger models than smaller models: I initially tried working with Llama 3.2-3B and Qwen 2.5-3B, since these are easy to fine-tune on a single A100, even with full-finetuning. However, Llama-3B had trouble following the format requirements and Qwen-3B seemed to plateau at a much lower accuracy. Both needed additional formatting (and other) reward functions, while the 8B model only needed a single reward function to track correctness.

- Reward hacking is annoying (but funny): With the 3B models, I had to include formatting reward functions, as well a negative reward for including any unnecessary text in the predicted list of genes. The Llama-3B model would quickly learn to optimize this reward by only a predicting a single gene name instead of a list of genes. This was pretty clever and avoided the unnecessary text penalty, but ignored the ranking task entirely.

- Models are quite sensitive to prompts: One odd observation was that Llama-8B zero shot performance is only 0.24. Looking into this, it was partly driven by a very long reasoning portion in 36% of examples, leaving no available tokens to predict the gene list given the token budget. Adding “use 200 words or less” to the reasoning section of the prompt reduced this problem to < 1% of examples, improving zero-shot performance to 0.38. Conversely, using the same reduced-reasoning prompt hurt performance for the binary reward GRPO model (0.48 -> 0.38), but had no effect on the rank-based reward GRPO.

Summary and Next Steps

We were able to show that RL can improve the performance of Llama models at causal gene identification, with reasonable cost ($50) and limited training data (~600 examples). While it doesn’t match the performance of the closed-source models yet, being able to do causal gene identification with private data and local models could be useful to speed up this interpretation of genetic analyses. It also shows the benefits of this approach in domains beyond math, and of using dense rewards using ranking instead of sparse rewards from correct/incorrect classification. In domains like biology where labeled data is often sparse, data-efficient approaches like GRPO/reinforcement learning could be a better fit than supervised fine-tuning.

Next Steps

There are a number of follow-up questions that could be interesting and are unexplored here.

- What does the LoRA learn that helps improve performance? In our preprint, we had seen that performance was partly driven by embedding similarity between the disease and causal gene. Maybe that baseline similarity improves with RL.

- Does the model-generated reasoning make sense? Is the reasoning component necessary? Could the reasoning component be shorter to reduce training time?

- Does majority voting at the inference stage instead of single inference outputs improve the performance even further? 8B inference is much faster than 70B, so we could generate more samples at inference time.

- Are there other tasks in biology or healthcare where similar RL fine-tuning approaches could work with small labeled datasets and custom reward functions?

If you want to try this yourself, check out the full implementation on GitHub. Contributions and feedback are always welcome!

Acknowledgements and Other References

This project was possible thanks to many open-source resources.

- trl from Hugging Face for the GRPO implementation.

- unsloth for the memory-efficient Llama-8B LoRA GRPO implementation and notebook.

- Simple GRPO notebook from @willccb.

Compute access was through Modal, thanks to Charles Frye for the Modal credits. These credits were part of the LLM fine-tuning course by Dan Becker and Hamel Hussain, thanks to them for the excellent fine-tuning course.